Sliding puzzle

The familiar click of plastic tiles sliding across a board has occupied human minds for nearly 150 years. What began as a simple mathematical curiosity in 1880 has transformed into something remarkably different—a puzzle genre where animated galaxies rotate, butterflies flutter, and sea waves crash within each moving piece.

- From numbered tiles to living images

- The video puzzle revolution

- Why your brain loves puzzle challenges

- Content that challenges and delights

- Progressive difficulty systems

- Technical achievement and market position

- Try it yourself

- Common questions

From numbered tiles to living images

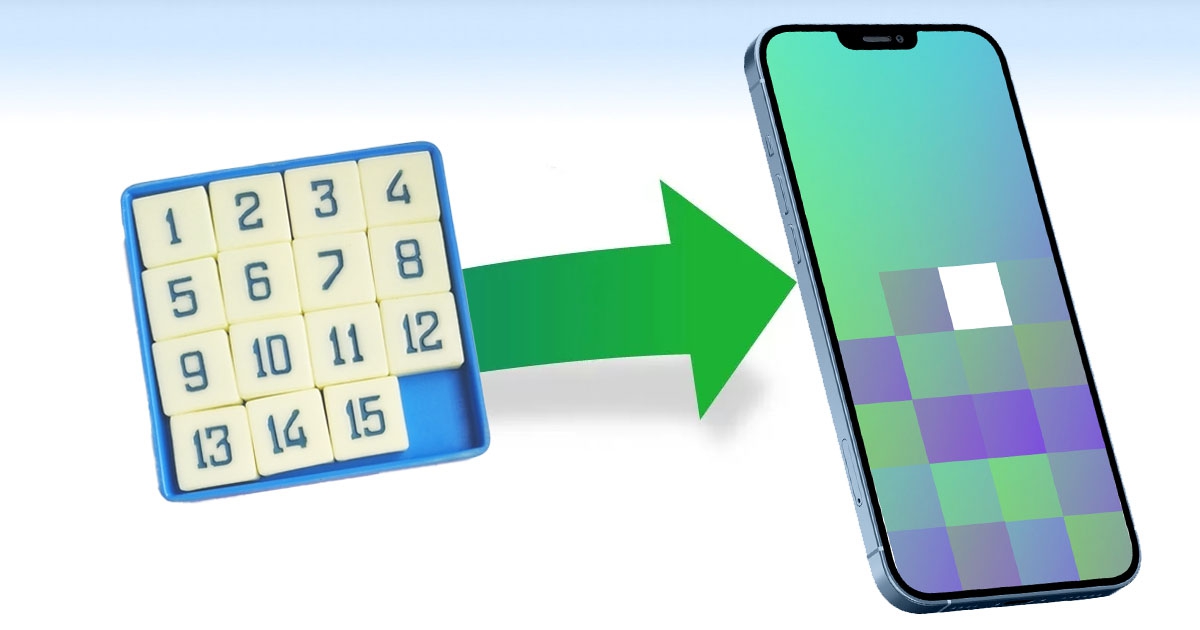

The sliding puzzle, invented by Noyes Chapman in 1880, sparked what historians call "puzzle mania" in the early 1880s. The original concept was straightforward: arrange 15 numbered tiles within a 4×4 grid by sliding them into the single empty space. Sam Loyd is often wrongly credited with making sliding puzzles popular based on his false claim that he invented the fifteen puzzle, but Chapman's creation stands as the true genesis of this enduring game type.

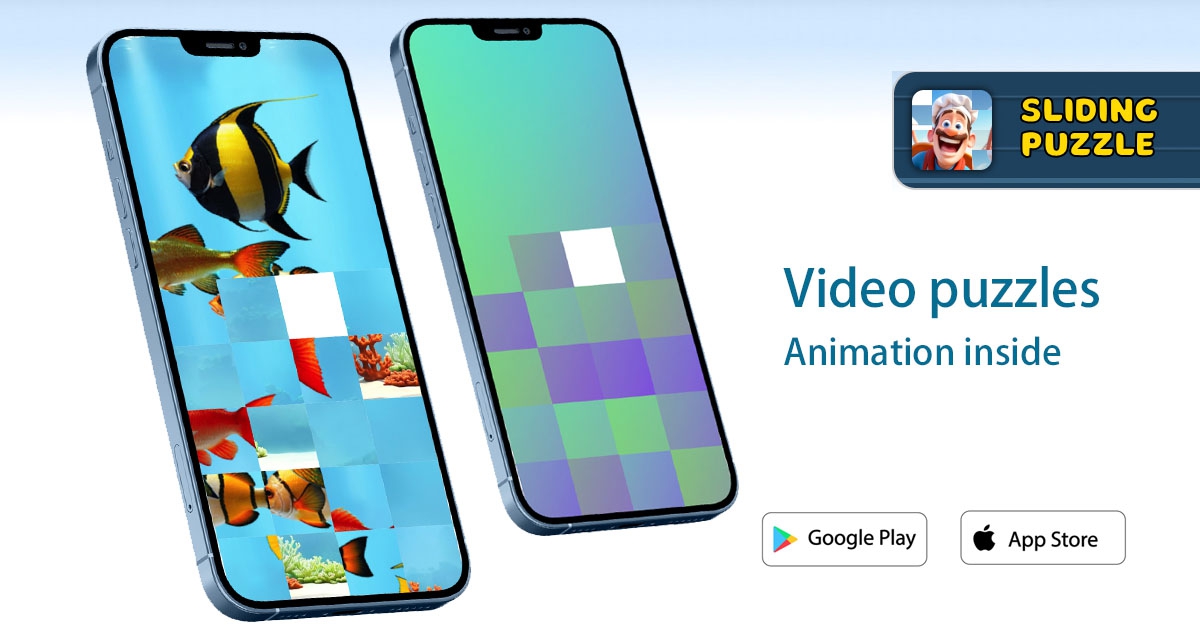

The video puzzle revolution

Why your brain loves puzzle challenges

Research into puzzle gaming reveals consistent cognitive benefits, though scientists emphasize the importance of understanding what these games actually train. Puzzle game playing activates the prefrontal lobe of the brain that is involved in thinking, attention, and decision-making, leading to improved cognitive intelligence, learning abilities, and decision-making, according to research published in PMC. The study measured measurable decreases in cortisol and alpha-amylase levels after puzzle gameplay, suggesting these games provide cognitive stimulation without inducing stress. A 2014 Nanyang Technological University study demonstrated that participants who played puzzle games for one hour daily showed significant executive function improvements. After 20 hours of game play, players of Cut the Rope could switch between tasks 33 per cent faster, were 30 per cent faster in adapting to new situations, and 60 per cent better in blocking out distractions and focusing on the tasks at hand. The research attributed these gains to puzzle mechanics that force players to continuously adapt strategies rather than repeat memorized patterns. The University of Colorado Boulder examined 1,241 individuals aged 28-49, finding that puzzle games had a particular association with processing speed. Their research controlled for sociodemographic factors and adolescent IQ to isolate genuine gameplay effects. However, Case Western Reserve University's Associate Professor Vera Tobin offers important context: The very best thing doing a puzzle trains you for is doing puzzles. But, practicing a specific cognitive skill—like word recall, recognizing spatial patterns or reading quickly in one activity—can transfer over into other activities that use that same skill. The key lies in novelty and challenge—repeating mastered puzzles provides diminishing returns. Research from Duke University School of Medicine and Columbia University found that participants, most of them around age 71, who trained in doing computerized crossword puzzles demonstrated greater cognitive improvement than those who were trained on computerized cognitive games, with particularly strong effects on memory function in adults with mild cognitive impairment. The pattern across multiple studies suggests puzzles work best when they challenge players to develop new strategies rather than repeat familiar patterns—precisely what video-based sliding puzzles enable through their dynamic, changing content.Content that challenges and delights

Progressive difficulty systems

Effective puzzle games scale challenge through multiple mechanisms. Grid size represents the most obvious variable—2×3 grids serve as gentle introductions, while 4×9 grids present formidable challenges even for experienced players. Obstacle tiles introduce spatial planning requirements. Players must route movable tiles around fixed positions, adding a chess-like strategic layer to spatial puzzles. Combined with video content, this creates scenarios where players simultaneously track motion patterns while planning movement paths around barriers. Move limits add another dimension. Each level provides a specific number of moves before triggering consequences. When moves expire, game characters appear and randomly redistribute four tiles, potentially undoing significant progress. This mechanic introduces interesting choice architecture: watch an advertisement to preserve tile positions, or accept the randomization and continue with refreshed moves. The move limit system deserves particular attention from game design perspectives. It creates natural tension without imposing time pressure, allowing thoughtful play while maintaining stakes. The advertisement choice offers a genuine decision point—players balance their current progress against interruption cost, adding meta-game consideration to puzzle-solving.Technical achievement and market position

Creating smooth video playback across multiple animated puzzle tiles represents genuine technical accomplishment. Each tile must maintain synchronization, respond instantly to touch input, and smoothly animate during slides—all while preserving battery life and ensuring compatibility across diverse devices. The computational requirements explain why this evolution took until the late 2020s to emerge. Earlier mobile devices lacked sufficient processing power to maintain quality and performance simultaneously. Modern chipsets finally provide the capability, but implementation still requires careful optimization. This technical barrier creates natural market differentiation. Traditional static sliding puzzles face intense competition—hundreds of similar applications exist across app stores. Video-based puzzles occupy a distinct category with minimal direct competition, offering clear value to players seeking novel challenges. The genre's evolution from numbered tiles to static images to animated video demonstrates how technological advances enable genuinely new gameplay experiences. This isn't merely improved graphics or smoother animations—it's fundamentally different cognitive challenges that couldn't exist in previous iterations.Try it yourself

Over 100 levels await across varying difficulty tiers. Start with numbered tile puzzles if you're new to the genre, progress to static images as spatial reasoning develops, then tackle animated content when ready for serious challenges.Common questions

Will playing puzzle games actually improve my cognitive abilities?

Research consistently shows measurable improvements in specific cognitive skills like spatial reasoning, processing speed, and executive function. However, as scientists emphasize, the greatest benefits come from challenging yourself with new puzzle types rather than repeating mastered ones. Video-based puzzles offer this novelty by introducing dynamic content that requires new solving strategies.

Are animated puzzles significantly harder than traditional ones?

Yes, particularly levels without static visual reference points. Gradient animations and abstract motion patterns force you to track changes over time rather than simply matching static images. This activates different cognitive processes—pattern recognition and temporal memory rather than just spatial reasoning. Most players find these levels considerably more challenging but also more engaging once they develop appropriate strategies.

How much time should I spend on puzzle games for cognitive benefits?

Research studies showing cognitive improvements typically involved 25 minutes to one hour of daily practice. However, the key factor isn't duration but challenge level. Spending an hour on puzzles you've mastered provides less benefit than 25 minutes tackling new, difficult content. The Nanyang Technological University study demonstrated significant improvements after 20 total hours of gameplay spread across several weeks—suggesting consistent, moderate practice beats marathon sessions.